The President’s Role in Improving Teaching and Learning

Blog Post

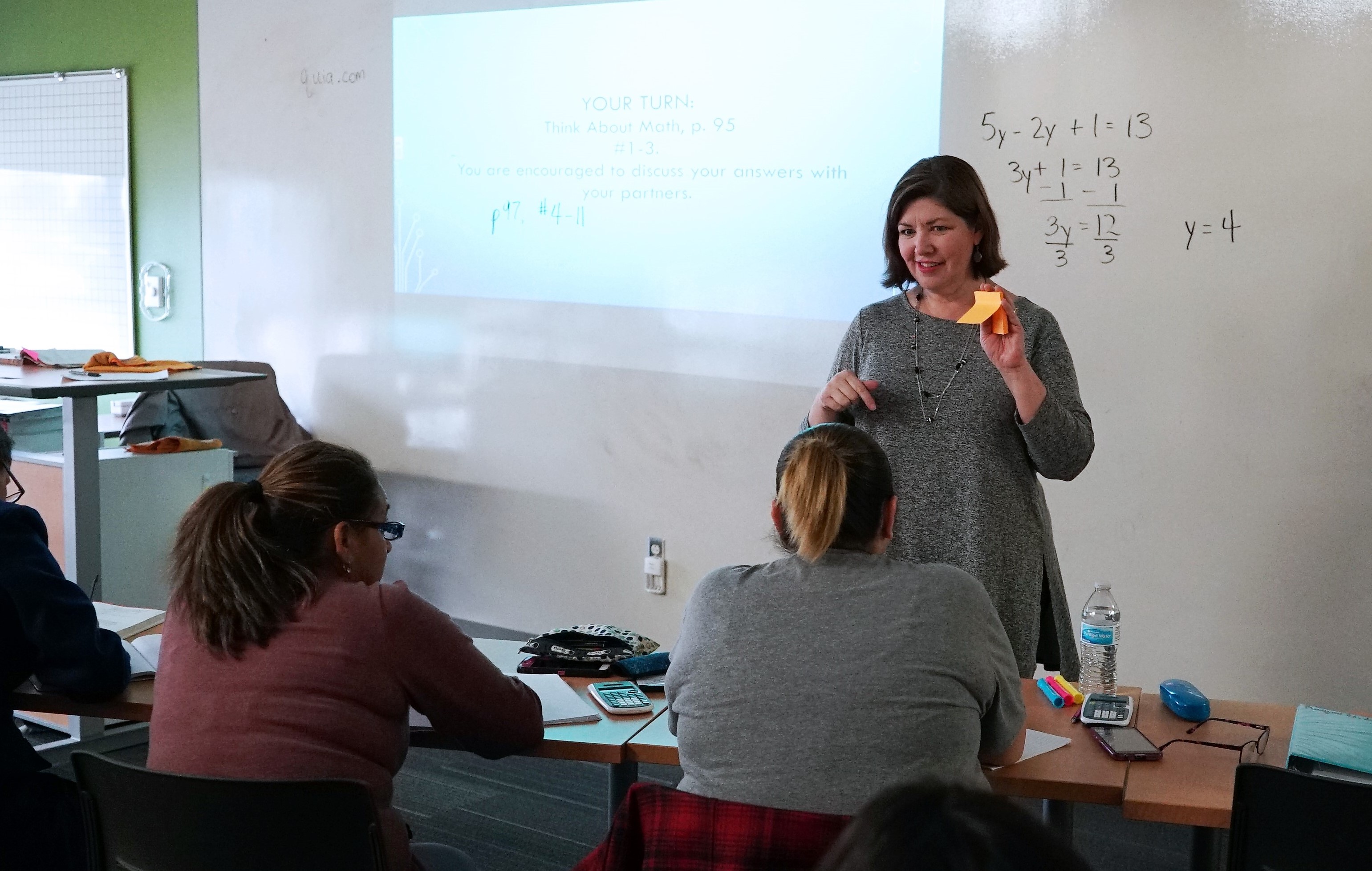

At each of the many community colleges I have visited over the past eight years, I’ve met excellent faculty who work hard to improve their craft so that more students learn. They structure courses so that students take on projects and critically and enthusiastically discuss ideas. They experiment with new approaches to pedagogy, measure the results, and shift course depending on student outcomes. They use inquiry-based methods to teach college-level math and English to students who might otherwise be stuck in old school remedial classes.

But this excellence isn’t the norm. Too often, instructors teach lecture-based courses that fail to engage or challenge students and that judge students by their performance on multiple choice tests. They don’t probe their own practice to continuously improve.

What distinguishes the colleges where most professors demonstrate strong teaching that results in higher levels of student learning? It’s not the existence of systems to assess student learning outcomes (sorry, accreditors) or a revamped general education curriculum. It is instead a culture that elevates teaching practice: systems that hire for and incentivize effective instruction, establish a common understanding of what excellent teaching is and aims to accomplish, and develop faculty through focused professional learning.

None of this happens without the commitment of the college president. Yes, that notion may seem counterintuitive. After all, it’s the faculty who—with their deans and program chairs—define the curriculum and set standards, and who must choose effective teaching methods so that more of their students succeed. But while deference to faculty autonomy displays an admirable respect for colleagues’ expertise, it also suggests a misunderstanding of one of the college president’s essential roles.

If large numbers of faculty are to continuously pursue excellence in teaching, presidents must embrace the importance of highly effective classroom education and have a strategy for scaling improvements in teaching and learning. From my observations in the field, here are some ways presidents fulfill that role:

- Understand the state of teaching and learning improvements. For presidents to engage with faculty on their campus about better teaching practice, they would do well to understand advances in teaching and learning elsewhere. How, for instance, did Odessa College achieve a 96 percent course completion rate with teaching methods centered on student connection and belonging? How is a college-wide approach to project-based learning helping to improve student success at Worcester Polytechnic Institute? How did learning improve at colleges that used Carnegie Mellon University’s technology-aided adaptive platform? Effective presidents don’t try to impose specific teaching practices, but they do ask questions and share what they learn in conversations with deans, department chairs, and faculty.

- Identify the great teachers. At colleges that scale excellent teaching and learning practices, exceptional faculty drive the agenda. Strong practitioners themselves, these faculty leaders value working collectively and understand that collaboration need not diminish their independence or force them to compromise on classroom rigor. At colleges that haven’t yet undertaken efforts to scale improvements in teaching and learning, many of the best teachers may initially prefer to be left alone, undistracted by committee participation or by processes that are compliance-oriented and unrelated to teaching practice. So, the president may need to seek them out. That means having conversations with deans, department chairs, and faculty who have been recognized for excellent teaching. As much as possible, presidents should enter these conversations with a learner’s mindset, lest faculty view them as precursors to accountability-oriented reforms.

- Elevate the leadership of exceptional faculty. Having identified potential faculty leaders, presidents must bring them to the center of reform. The president of Valencia College did this by having faculty define the six qualities of excellent instructors that would shape a revamped tenure system. (See page 13 of Building a Faculty Culture of Student Success.) At West Kentucky Community and Technical College, the president charged exceptional faculty with crafting the plan for improvements in teaching and learning in the college’s accreditation process. As a result, every faculty member is trained on improving methods for reading instruction. In these and other cases, presidents issued a charge to a workgroup of excellent faculty that clearly prioritized college-wide improvements in teaching and learning. In doing so, they also signaled the strong likelihood of presidential support—including funding—for whatever faculty recommended.

- Institutionalize reforms. Highly effective presidents consider the role of systems when developing a culture that prizes teaching and learning. An obvious and excellent place to start is with a well-resourced teaching and learning center. Pierce College went even further, negotiating a faculty contract that ties pay increases to participation in college-created professional development. Odessa College centralized its professional development dollars—which elsewhere tend to be meted out with little alignment to institutional goals—to support faculty training to improve students’ sense of belonging. And Valencia College tied its six instructor competencies not just to the new tenure system but also to its hiring processes, the offerings at its teaching and learning center, and post-tenure review.

Presidents don’t decide how courses are taught or what the core of teaching and learning reform will be. But their leadership and their unique responsibilities make them indispensable to ensuring an approach to teaching and learning reform that extends college-wide. In the end, if the president doesn’t convey the importance of exceptional teaching and learning and align the institution’s resources toward that goal, nobody will, and the exceptional teaching practices of great faculty will never scale.

This essay was originally published by the Community College Research Center as part of a series about high-quality instruction in community colleges.